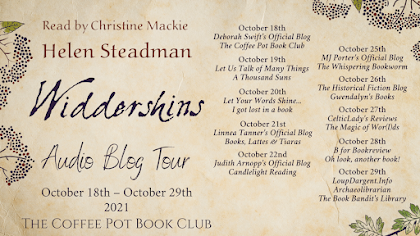

The new audiobook of Widdershins is narrated brilliantly by

talented actor, Christine Mackie, from Downton Abbey, Coronation Street, Wire

in the Blood, and so on.

The first part of a two-part series, Widdershins is inspired by the Newcastle witch trials, where sixteen people were hanged. Despite being the largest mass execution of witches on a single day in England, these trials are not widely known. In August 1650, fifteen women and one man were hanged as witches after a Scottish witchfinder found them guilty of consorting with the devil. This notorious man was hired by the Puritan authorities in response to a petition from the Newcastle townsfolk who wanted to be rid of their witches.

Widdershins is told through the eyes of Jane Chandler, a young woman accused of witchcraft, and John Sharpe, the witchfinder who condemns her to death. Jane Chandler is an apprentice healer. From childhood, she and her mother have used herbs to cure the sick. But Jane soon learns that her sheltered life in a small village is not safe from the troubles of the wider world. From his father’s beatings to his uncle’s raging sermons, John Sharpe is beset by bad fortune. Fighting through personal tragedy, he finds his purpose: to become a witchfinder and save innocents from the scourge of witchcraft.

Praise for Widdershins:

The Historical Novel Society said of Widdershins: “Impeccably written, full of herbal lore and the clash of ignorance and prejudice against common sense, as well as the abounding beauty of nature, it made for a great read. There are plenty of books, both fact, and fiction, available about the witch-trial era, but not only did I not know about such trials in Newcastle, I have not read a novel that so painstakingly and vividly evokes both the fear and joy of living at that time.”

Trigger Warnings:

Domestic abuse, rape, torture, execution, child abuse, animal abuse, miscarriage, death in childbirth.

Buy Links

Amazon UK Amazon US Amazon CA Amazon AU Audible Blackwells Waterstones

Kobo iBooks iTunes Foyles Book Depository Universal eBook Link

¸.•*´¨)✯ ¸.•*¨) ✮ ( ¸.•´✶

Helen Steadman

Thanks

very much, Mary Ann for interviewing me on your blog. While thinking up five

fun things for you, I’m enjoying a lovely morning coffee while looking out of

my window at the hills and forests of Durham and Northumberland, which is where

Widdershins is mostly set.

Fun fact #1: I once trained in tree medicine

When I decided that the witches in my book would be wise women who used herbs to heal, I thought it would be a good idea to learn more about herbal remedies. Luckily, I live only fifteen miles away from Dilston Physic Garden, which is renowned for its herbal training courses and research. I signed up for a couple of courses and spent time learning to identify trees and plants correctly (very important), and I then went on to harvest berries, bark, and leaves, which I turned into various remedies. I was very impressed with tree medicine and you’ll see many instances of it in Widdershins and in its sequel, Sunwise.

I

also set up my own mini physic garden, which I call my magic tea garden. This

contains a dozen or so herbs, which I grew so I could learn about plant cycles

and growing, harvesting, drying, and preparing herbs. They also make a lovely

cup of tea. (Please be very careful before using any plants as many are

poisonous and even the safe ones can be risky if you’re pregnant, on

medication, or have an illness or condition. In addition, some safe plants

resemble toxic ones, so please get advice from a professional before harvesting

berries, flowers, leaves, bark, and seeds.)

Fun Fact #2: I’ve forged a sword

Spurred on by my experience of learning about herbal medicine, when I came to write my third book, The Running Wolf, which is about a German swordmaker who wound up in an English prison, I decided to train in blacksmithing. I started off by making a pendant, a fire steel, and a rat-tailed poker. I made the poker using a power hammer, which was especially exciting.

Then, I went on to hand forge my own sword. This was extremely difficult work, and even though I had a lot of help, I’ve never been so physically exhausted in my life. I’ve also never been so hot in my life. Hats off to anyone who forges metal whether for work or pleasure (or both). If you look closely at the photo of me holding my sword, you’ll notice my sooty fingernails and the various grazes on my hands. If you think I look rather clean in this photo, this is because I’d finished the sooty forge work and had spent the day filing the bronze handle.

Fun Fact #3: I can say Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogogoch

This is the name of the longest place name in Europe (and the second-longest in the world, by all accounts). It’s a small village on the Welsh island, Anglesey (Ynys Môn, in Welsh). My maternal grandfather was from a nearby village on Anglesey. During a childhood visit, and after much pleading, he taught me how to say it and I proudly got on the bus one day and asked the driver for a ticket to Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogogoch. He gave me a long-suffering look and replied, ‘Llanfair PG would’ve done, love.’ Although my grandfather’s first language was Welsh, I only know a few words, and most of them aren’t suitable for sharing here…

Fun Fact #4: I’m terrified of flying

This isn’t really that much fun now I come to think of it. I enjoy the experience of flying, but I’m always very anxious about what might possibly go wrong. I’ve tried hard not to pass on this fear to my children, but I expect the sight of my white knuckles gripping the armrest for dear life might be a bit of a giveaway. I was very pleased with myself when I flew solo to Germany to research one of the locations for my third book. I wasn’t too bad going out, but I was quite anxious coming back. It must have shown on my face because I was taken to one side at the airport and searched in front of everyone, which included having to take off my boots. I’ve always wanted to go to New York City, and I’m determined to pluck up the courage to do it, once Covid-19 is less of a threat. Although I might have to ask the airline whether they do a ‘sedate and crate’ option.

Fun Fact #5: I have two dogs, with only three ears between them

This one doesn’t sound like much fun either, but it has a happy ending. When I went to the dog’s home to pick up Elsie, I went into the kennels where all the dogs live, one per cage. Before I reached Elsie’s cage, I spotted Eddie, who was jumping up and down in his cage, with his front paws in the air, desperate for a new home. His little ears were bald and he looked so pitiful. The dog’s home told me he’d been born on the streets and that he and his mother had been brought to the home. He’d been adopted twice, but then rejected each time and returned to the dog’s home. So, I took him home too.

With a bit of TLC, his bald ears healed and turned into the delightful, silky ginger ears you see today. Elsie only has one ear and I worried that she’d been involved in some awful dogfighting or something but the vet said it was most likely she’d been born that way as she was missing the inner cartilage, too. Despite having only one ear, Elsie has excellent balance and she can hear the snack tin opening from the far end of the garden, no matter how carefully I remove the lid. And she always seems to attract a few extra pats from people we meet on dog walks.

Dr. Helen Steadman

Dr. Helen Steadman is a historical novelist. Her first novel, Widdershins, and its sequel, Sunwise were inspired by the Newcastle witch trials. Her

third novel, The Running Wolf was inspired by a group of Lutheran

swordmakers who defected from Germany to England in 1687.

Despite the Newcastle witch trials being the largest mass execution of witches on a single day in England, they are not widely known about. Helen is particularly interested in revealing hidden histories and she is a thorough researcher who goes to great lengths in pursuit of historical accuracy. To get under the skin of the cunning women in Widdershins and Sunwise, Helen trained in herbalism and learned how to identify, grow and harvest plants and then made herbal medicines from bark, seeds, flowers, and berries.

The Running Wolf is the story of a group of master swordmakers who left Solingen, Germany, and moved to Shotley Bridge, England in 1687. As well as carrying out in-depth archive research and visiting forges in Solingen to bring her story to life, Helen also undertook blacksmith training, which culminated in making her own sword. During her archive research, Helen uncovered a lot of new material and she published her findings in the Northern History journal.

Helen is now working on her fourth novel.

Social Media Links

Website Twitter Facebook Instagram Amazon Author Page Goodreads YouTube

Christine Mackie has worked extensively in TV over the last thirty years in well-known TV series such as Downton Abbey, Wire in the Blood, Coronation Street, French & Saunders and The Grand. Theatre work includes numerous productions in new writing as well as classics, such as A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Comedy of Errors, Richard III, An Inspector Calls, and the Railway Children. In a recent all-women version of Whisky Galore, Christine played three men, three women, and a Red Setter dog!

Social Media Links