History Extra

Tamora – Titus Andronicus

Tamora, Queen of the Goths, is a cruel and brutal central player in Shakespeare’s ultimate revenge tragedy, Titus Andronicus. Her ruthless, bloody-minded scheming leads to a gore-fest worthy of Game of Thrones.

We are introduced to Tamora as a conquered queen, begging the general of Rome, Titus Andronicus, to show her captured sons mercy. When Titus refuses and instead executes her sons he unleashes a maelstrom of vengeance, as Tamora becomes fuelled by the need to wreak revenge on Titus and his family.

Tamora is patient in her quest for vengeance. She secures herself a powerful position by marrying the weak-willed emperor Saturninus, who she manipulates as a political pawn while conducting an illicit relationship with Aaron, her equally scheming lover.

Tamora’s villainy reaches a shocking peak when she orders her two surviving sons to rape and mutilate Titus’s daughter Lavinia, cruelly ignoring the innocent girl’s pleas for mercy and mocking her distress. In one of Shakespeare’s most shocking and disturbing moments, Lavinia emerges with her hands cut off and her tongue removed. In a 2014 production at London’s Globe Theatre the gore was so overwhelming that during the course of the 51-show run 100 audience members reportedly either fainted (including the reviewer from The Independent) or had to leave.

Tamora gets her comeuppance in one of Shakespeare’s most outrageously blood-soaked finales: Titus murders her two sons and serves them to her baked in a pie. After unwittingly eating the pie Tamora is stabbed to death, as the final scene descends into a bloodbath.

Angelo – Measure for Measure

At first glance Angelo appears quite unlike any of Shakespeare’s other villains: a puritanical moral crusader whose righteousness (and name) seems almost otherworldly. He appears immune to sins of the flesh, described in Act I as “a man whose blood/ is very snow-broth; one who never feels/ the wanton stings and motions of the sense.” However, we quickly come to discover that the upright Angelo is not as virtuous as he first seems.

As temporary leader of Vienna, Angelo proves harsh and unforgiving. He takes a malevolent delight in dishing out severe justice, proclaiming in one scene: “hoping you’ll find good cause to whip them all”.

One way in which Angelo asserts his authority is by cracking down on the city’s sexual immorality, sentencing the young Claudio to death for impregnating his lover. But when Claudio’s virtuous sister Isabella comes to beg for mercy for her brother, Angelo’s intense hypocrisy is revealed. Consumed by lust for Isabella he propositions her, claiming he will reprieve Claudio if she agrees – and if not, her brother’s death is guaranteed to be slow and tortuous.

Revelations from Angelo’s past highlight further his cruel nature, as the audience learns that he abandoned his fiancée when her dowry was lost in a shipwreck.

However, Angelo is not entirely incorrigible. He is willing to confess his sins and expresses guilt, stating in Act V, Scene I “I crave death more willingly than mercy”. Furthermore, none of his immoral plans come to fruition; Isabella is not seduced and Claudio is not executed. Despite his corrupt lust and serious hypocrisy, he is one of Shakespeare’s few villains to be granted forgiveness. The Duke of Vienna pardons his crimes and repeals his death sentence, on the condition that he marries the mistress he abandoned.

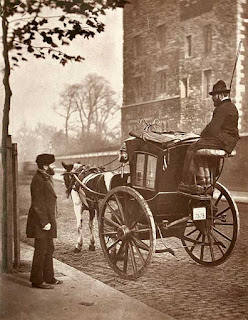

1603-4 engraving of a scene from Measure For Measure. (Archive photos/ Getty images)

Richard III – Richard III

Despite having little grounding in historical fact, Shakespeare’s depiction of Richard III as a Machiavellian villain who had a physical deformity, lusted after his niece and lost his “kingdom for a horse” has had real sticking power.

A malicious, deceptive and bitter usurper who seizes England’s throne by nefarious means, Shakespeare’s Richard takes delight in his own villainy. He is unabashed in his evil motives, shamelessly proclaiming in his famous “Now is the winter of our discontent” speech: “I am determined to prove a villain”. However, Richard is also an undeniably charming and complex figure who sucks in the audience with his immoral logic and dazzling wordplay.

But Richard’s sins come back to haunt him – quite literally. Shakespeare provides us a long list of Richard’s murder victims, in a roll call of ghosts that visit him on the last night of his life. Edward of Westminster; Henry VI; George, Duke of Clarence; Earl Rivers; Richard Grey; Thomas Vaughan; Lord Hastings; the princes in the Tower; the Duke of Buckingham and Queen Anne Neville are all claimed to have been murdered by the king.

Writing for History Extra, John Ashdown-Hill suggests that Shakespeare’s claims here are both unfair and untrue. He suggests that some of Richard’s alleged victims (Clarence, Rivers, Grey, Vaughan and Buckingham) were legitimately and legally executed, while “there is no evidence that Edward of Westminster, Henry VI, the princes in the Tower or Anne Neville were murdered by anyone”.

Immediately after his visitation by spirits – the evening before his downfall and death – Richard appears to be suddenly struck by doubt. Despite the glee he formerly took in his wrongdoing, he suddenly lacks conviction about his actions: “O no, alas, I rather hate myself/ For hateful deeds committed by myself/ I am a villain”.

Goneril and Regan – King Lear

Described by their own father as “unnatural hags”, Goneril and Regan are two grasping, self-interested and power-hungry daughters of King Lear. Their willingness to betray their father and their honest sister Cordelia causes the collapse of a kingdom and ultimately leads to Lear’s descent into madness.

In the play’s opening scene the elderly Lear declares his intention to step down as king and divide his realm between his three daughters. In response to this, Goneril and Regan cleverly charm their father, hoping to grasp all they can from his inheritance. Falling for their superficial flattery, Lear divides his kingdom between the two of them, disinheriting Cordelia, who claims she cannot express her love for her father in words. This proves to be a fatal mistake, as Goneril and Regan’s feigned loyalty dissolves rapidly and their willingness to betray their father quickly becomes clear.

By Act III the sisters’ ruthless political manoeuvrings have descended into outright violence. Regan and husband, the Duke of Cornwall, torture her father’s supporter Gloucester, plucking out his eyes and turning him out to wander blindly in the wild. Cornwall’s gruesome exclamation of “Out, vile jelly!” as he rips out the old man’s eyes, is one of the play’s most memorable – and horrifying – moments.

Goneril and Regan’s malevolence eventually turns inwards and rips them apart. Fuelled by jealousy at her sister’s supposed relationship with Edmund (another central villain of the play), Goneril poisons Regan and then kills herself.

Lady Macbeth – Macbeth

Lady Macbeth is undoubtedly one of Shakespeare’s most fascinating female characters. Driven towards evil by a deep ambition and a ruthless appetite for power, she uses her sexuality and powers of manipulation to exert a corrosive influence over her husband, Macbeth.

Arguably a more compelling character than her husband, Lady Macbeth is generally viewed as the driving force behind Macbeth’s lust for power. While he is plagued by uncertainty about killing those who stand in his way, his wife is altogether stronger in her immoral convictions. She persuades him to pursue the Scottish throne by violent and deceptive means, telling him to “look like th' innocent flower/ but be the serpent under't”.

Lady Macbeth encourages her husband’s wrongdoing by portraying murder as both the logical and brave course of action, telling him to “Screw your courage to the sticking place/and we’ll not fail”. After Macbeth murders King Duncan (to claim his throne) she reassures him that “what’s done, is done” and cleans up the murder scene when Macbeth is too afraid to do so. At other points in the play Lady Macbeth’s manipulation of her husband descends into outright bullying. In an intriguing reversal of gender roles she dismisses her husband’s anxiety as feminine weakness, mockingly asking “are you a man?” in response to his hesitation.

Like many of Shakespeare’s villains, Lady Macbeth is eventually consumed by her guilty conscience and driven mad by her murderous actions. Plagued by episodes of sleepwalking, she wanders through the castle, unable to rid the image of her bloodstained hands from her mind, muttering: “Out damn’d spot… who would have thought the old man to have had so much blood in him?” This is our last image of Lady Macbeth – in the play’s final act she becomes disappointingly absent, eventually committing suicide offstage.

Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth, in a 1906 painting by John Singer Sargent. (Print Collector/Getty Images)

Claudius – Hamlet

In the first act of Hamlet, Shakespeare tells his audience “something is rotten in the state of Denmark”. We quickly discover that this is a reference to Denmark’s usurper king – and Hamlet’s uncle – Claudius.

A crafty politician determined to maintain his grasp over his kingdom, Claudius is guilty of the ultimate sin – fratricide. He has secretly murdered his brother, the king (Hamlet’s father), pouring poison into his ear as he slept, in order to claim his throne and steal his wife.

But, like Macbeth and Richard III, Claudius too is plagued by the vengeful ghost of his victim. The spirit of the dead king appears to Hamlet, demanding to be avenged and exposing Claudius as “that incestuous, that adulterate beast/ with witchcraft of his wit, with traitorous gifts...”.

Shakespeare has crafted a particularly intriguing villain in Claudius by giving him a conscience. Unlike Iago, Tamora or Richard III, Claudius takes no pleasure in his wrongdoing. In Act III he expresses his guilt when he confesses his sins in prayer: “O, my offence is rank, it smells to heaven”.

King Claudius ultimately falls victim to his own conniving nature, as his wife, Gertrude (Hamlet’s mother, who many critics suggest Claudius genuinely loves), accidentally drinks from a poisoned chalice Claudius had intended for Hamlet. Claudius, too, meets his bitter end in classic bloody Shakespearean form: Hamlet stabs Claudius with a poisoned sword before forcing him to drink from the poisoned chalice.

Iago – Othello

Many scholars see Iago as the most inherently evil of all Shakespeare’s villains. He spends the course of the play relentlessly plotting Othello’s downfall and his malicious scheming drives the storyline towards its tragic finale.

What proves so compelling about Iago is that his motivations for such insidious and calculated scheming seem unclear – his only desire appears to be Othello’s destruction. He accomplishes this by planting the seed of jealousy in Othello’s mind. He plots to “pour pestilence into his ear” in order to turn him against his wife, Desdemona. Skillfully concealing his nefarious intentions while winning Othello’s trust, Iago constructs a web of lies to make Othello believe in Desdemona’s sexual infidelity.

The consequences of Iago’s insidious influence are devastating. Enraged by jealousy, Othello eventually murders Desdemona and then kills himself. Although Iago’s schemes are eventually revealed and he is sentenced to execution, it is too little, too late, as his plans have already reached their disastrous conclusion.

Shakespeare does provide some reasons for Iago’s actions: that Othello passed him over for a military promotion and may have slept with his wife. However, it is generally agreed that none of these explanations are really fleshed out enough to provide a convincing motive for Iago’s scheming and profound hatred of Othello. Instead, Iago seems to have an intense enjoyment of manipulation and maliciousness for its own sake, perhaps making him the most essentially evil of all Shakespeare’s villains.

.jpg)