The failure of the Spanish Armada campaign of 1588 changed the course of European history. If the Duke of Parma’s 27,000-strong invasion force had safely crossed the narrow seas from Flanders, the survival of Elizabeth I’s government and Protestant England would have looked doubtful indeed.

If those battle-hardened Spanish troops had landed, as planned, near Margate on the Kent coast, it is likely that they would have been in the poorly defended streets of London within a week, and that the queen and her ministers would have been captured or killed. England would have reverted to the Catholic faith and there may have been no British empire.

It was bad luck, bad tactics and bad weather that defeated the Spanish Armada – not the derring-do displayed on the high seas by Elizabeth’s intrepid sea dogs. But it was a near-run thing.

Because of Elizabeth’s parsimony, driven by an embarrassingly empty exchequer, the English ships were starved of gunpowder and ammunition and so failed to land a killer blow on the ‘Great and Most Fortunate Navy’ during nine days of skirmishing up the English Channel in July and August 1588.

Only six Spanish ships out of the 129 that sailed against England were destroyed as a direct result of naval combat. However, a minimum of 50 Armada ships (probably as many as 64) were lost through accident or during the Atlantic storms that scattered the fleet en route to England and as it limped, badly battered, back to northern Spain.

More than 13,500 sailors and soldiers did not come home – the vast majority victims not of English cannon fire, but of lack of food and water, virulent disease and incompetent organisation.

Thirty years before, when Philip II of Spain had been such an unenthusiastic husband to Mary I, he had observed: “The kingdom of England is and must always remain strong at sea, since upon this the safety of the realm depends.”

Elizabeth knew this full well and gambled that her navy, reinforced by hired armed merchantmen and volunteer ships, could destroy the invasion force at sea. Her warships, she maintained, were the walls of her realm, and they became the first and arguably her last line of defence.

Decades of neglect had rendered most of England’s land defences almost useless against an experienced and determined enemy. In March 1587, the counties along the English Channel had just six cannon each. A breach in the coastal fortifications at Bletchington Hill, Sussex, caused 43 years before in a French raid, was still unrepaired.

England had no standing army of fully armed and trained soldiers, other than small garrisons in Berwick on the Scottish borders, and in Dover Castle on the Channel coast. Moreover, Elizabeth’s nation was divided by religious dissent – almost half were still Catholic and fears of them rebelling in support of the Spanish haunted her government.

Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, was appointed to command Elizabeth’s armies “in the south parts” to fight not only the invaders but any “rebels and traitors and other offenders and their adherents attempting anything against us, our crown and dignity…” and to “repress and subdue, slay or kill and put to death by all ways and means” any such insurgents “for the conservation of our person and peace”.

Some among Elizabeth’s subjects placed profit ahead of patriotism. In 1587, 12 English merchants – mostly from Bristol – were discovered supplying the Armada “to the hurt of her majesty and undoing of the realm, if not redressed”. Nine cargoes of contraband, valued between £300 and £2,000, contained not just provisions but also ammunition, gunpowder, muskets and ordnance. What happened to these traders (were they Catholics?) is unknown, but in those edgy times, it’s unlikely they enjoyed the queen’s mercy.

Elsewhere, Sir John Gilbert, half-brother to Sir Walter Ralegh, refused permission for his ships to join Sir Francis Drake’s western squadron and allowed them to sail on their planned voyage in March 1588 in defiance of naval orders.

If that wasn’t bad enough, Elizabeth’s military advisers – unaware that Parma planned to land on the Kent coast – decided on Essex as the most likely spot where the Spanish would storm ashore.

A contemporary painting of English ships and the Spanish Armada, which, so one Tudor verse had it, bore sailors “that were full of the pox”. (Bridgeman)

Breaking barriers

The Thames estuary had a wide channel leading straight to the heart of the capital, bordered by mud flats that posed a major obstacle to a vessel of any draught. Therefore, defensive plans included the installation of an iron chain across the river’s fairway at Gravesend in Kent, designed by the Italian engineer Fedrigo Giambelli. This boom, supported by 120 ship’s masts (costing £6 each) driven into the riverbed and attached to anchored lighters, was intended to stop enemy vessels penetrating upriver to London. Yet it would do no such thing – for it was broken by the first flood tide.

A detailed survey of potential invasion beaches along the English Channel produced an alarming catalogue of vulnerability. In Dorset alone, 11 bays were listed, with comments such as: “Chideock and Charmouth are two beaches to land boats but it must be very fair weather and the wind northerly.” Swanage Bay could “hold 100 ships and [the anchorage is able] to land men with 200 boats and to retire again without danger of low water at any time.”

Lacking time, money and resources, Elizabeth’s government could only defend the most dangerous beaches by ramming wooden stakes into the sand and shingle as boat obstacles, or by digging deep trenches above the high water mark. Mud ramparts were thrown up to protect the few cannon available, or troops armed with arquebuses (an early type of musket) or bows and arrows.

Fortifications on the strategically vital Isle of Wight were to be at least four feet (1.22m) high and eight feet (2.44m) thick, with sharpened poles driven into their face and a wide ditch dug in front. But its governor, Sir George Carey, had just four guns and gunpowder enough for only one day’s use.

Portsmouth’s freshly built ramparts protecting its land approaches had been severely criticised by Ralegh and were demolished, much to Elizabeth’s chagrin. New earth walls were built in just four months, bolstered by five stone arrow-head-shaped bastions behind a flooded ditch. Yet, more than half Portsmouth’s garrison were rated “by age and impotency by no way serviceable”, and the Earl of Sussex escaped unhurt when an old iron gun (supposedly one of his best cannon), blew into smithereens. In November 1587, Sussex complained that the town’s seaward tower was “so old and rotten” that he dared not fire one gun to mark the anniversary of the queen’s accession.

The network of warning beacons located throughout southern England since at least the early 14th century was overhauled. The iron fire baskets mounted atop a tall wooden structure on earth mounds were set around 15 miles (24km) apart. Kent and Devon had 43 beacon sites, and there were 24 each in Sussex and Hampshire.

These were normally manned during the kinder weather of March to October by two “wise, vigilant and discreet” men in 12-hour shifts. Surprise inspections ensured their diligence, and they were prohibited from having dogs with them, for fear of distraction.

It was a tedious and uncomfortable patriotic duty. A new shelter was built near one Kent beacon when a old wooden hut fell down. This was intended to protect the sentinels only from bad weather and had no “seats or place of ease lest they should fall asleep. [They] should stand upright in… a hole [looking] towards the beacons.” Not everyone spent their time scanning the horizon for enemy ships: two watchers at Stanway beacon in Essex preferred catching partridges in a cornfield and were hauled up in court.

An English chart shows the Spanish fleet off the coast of Cornwall. Much of the local militia slunk away when the Armada cleared the county. (National Maritime Museum)

Malicious firing

In July 1586, five men were accused of plotting to maliciously fire the Hampshire beacons “upon a [false] report of the appearance of the Spanish fleet” and in the ensuing tumult, to steal food “to redress the current dearth of corn”; engage in a little light burglary of gentlemen’s houses and liberate imprisoned recusants at Winchester. Most were gaoled but some were sent to London for further interrogation, for fear of a wider conspiracy.

Elizabeth’s militia makes the enthusiastic Local Defence Volunteers of ‘Dad’s Army’ during the Nazi invasion scare of 1940 look like a finely honed war machine. A census in 1588 revealed only 100 experienced “martial men” were available for military service and, as some had fought in Henry VIII’s French and Scottish wars of 40 years before, these old sweats were considered hors d’combat.

Infantry and cavalry were drawn from the trained bands and county militia. A thousand unpaid veterans from the English army in the Netherlands were recalled but they soon deserted to hide in the tenements of Kent’s Cinque Ports.

Militia officers were noblemen and gentry whose motivation was not only defence of their country, but protection of their own property too. Many living near the coast believed it more prudent to move their households inland than stay and fight on the beaches but were ordered to return “on pain of her majesty’s indignation, besides forfeiture of [their] lands and goods…”

The main army was divided into two groups. The first, under Leicester, with 27,000 infantry and 2,418 cavalry, would engage the enemy once he had landed in force. The second and larger formation, commanded by the queen’s cousin Lord Hunsdon, totalled 28,900 infantry and 4,400 cavalry. They were recruited solely to defend the sacred person of Elizabeth herself, who probably planned to remain in London, with Windsor Castle as a handy bolt hole if the capital fell.

An anonymous correspondent suggested to Elizabeth’s ministers that the best means to resist invasion was “our natural weapon” – the bow and arrow. It had defeated the French at Agincourt in 1415; why not the Spanish in 1588? One can imagine an old buffer, bristling at this threat to hearth and home, insisting that the bow and crossbow were “terrible weapons” which Parma’s mercenaries had not faced before. After further reflection, he concluded that “the most powerful weapon of all against this enemy was the fear of God”.

In the event, despite strenuous efforts to buy weapons in Germany, and arquebuses from Holland at 23s 4d (£1.17p) each, many militiamen were armed only with bows and arrows. A large proportion was unarmed and untrained. To avoid the dangers of fifth-columnist recusants in the militia ranks, every man had to swear an oath of loyalty to Elizabeth in front of their muster-masters.

Captain Nicholas Dawtrey, sent to train the Hampshire militia, warned that if 3,000 infantry crossed the Solent to defend the Isle of Wight, the Marquis of Winchester would be left “utterly without force of footmen other than a few billmen (with pole arms) to guard and answer all dangerous places”.

However, local people complained about being posted away from home, they and their servants being compelled “to go either to Portsmouth or Wight upon every sudden alarm, whereby their houses, wives and children shall be left without guard and left open by their universal absence to all manner of spoil”.

Hampshire eventually raised 9,088 men but Dawtrey pointed out that “many… [were] very poorly furnished; some lack a head-piece [helmet], some a sword, some one thing or other that is evil, unfit or unseemly about him”. Discipline was also problematic: the commander of the 3,159-strong Dorset militia (1,800 totally untrained) firmly believed they would “sooner kill one another than annoy the enemy”.

When the Armada eventually cleared Cornwall, some of the Cornish militia, ordered to reinforce neighbouring counties, thought they had done more than enough to serve queen and country. Their minds were on the harvest and these reluctant soldiers decided to slink away from their commanders and their colours.

The Spanish were now someone else’s problem.

Map Illustration by Martin Sanders.

Armada propaganda

Why it paid to vilify the perfidious Spanish

The Tudor propaganda machine became strident as the Spanish fleet appeared, delivering terrifying warnings of genocide to stiffen a fearful population’s resistance.

Spanish spies reported that Elizabeth’s ministers, “being in great alarm, made the people believe that the Spaniards [are] bringing a shipload of halters in the Armada to hang all Englishmen and another shipload of scourges to whip women”.

As the skirmishes continued in the Channel, foreigners were placed under curfew and had their shops closed up. An Italian, harassed in the streets, maintained it was easier “to find flocks of white crows than one Englishman who loves a foreigner”.

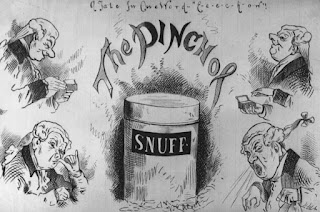

A pamphlet entitled A Skeltonical Salutation reassured its readers that fish that consumed the flesh of drowned Spaniards would not be infected by their venereal diseases. The doggerel verse asked whether:

“this year it were not best to forebear

On such fish to feed

Which our coast doth breed

Because they are fed

With carcase dead

Here and there in the rocks

That were full of the pox…

Our Cods and Conger

Have filled their hunger

With the heads and feet

Of the Spanish fleet

Which to them were as sweet

As a goose to a fox…”

Thomas Deloney’s A Joyful New Ballad described Spanish perfidy:

“Our wealth and riches, which we enjoyed long;

They do appoint their prey and spoil by cruelty and wrong

To set our houses afire on our heads

And cursedly to cut our throats

As we lie in our beds

Our children’s brains to dash against the ground”

Another tract was said to have been found “in the chamber of Richard Leigh, a seminary priest lately executed for high treason”. In reality, his identity was stolen for propaganda purposes. The ‘tract’ claimed that English naval supremacy and the omnipotence of England’s Protestant God were undeniable. “The Spaniards did never take or sink any English ship or boat or break any mast or took any one man prisoner.” As a result, Spanish prisoners believed that “in all these fights, Christ showed himself a Lutheran”.

Armada commander Medina Sidonia attracted special vilification. He spent much of his time “lodged in the bottom of his ship for his safety”.

What if the Armada had got through?

England’s poorly armed militia and uncompleted defences could have been overwhelmed by Spanish invaders, after landing in Kent with the heavy siege artillery carried by the Armada.

Based on the progress of his 22,000 troops – when they covered 65 miles in just six days after invading Normandy in 1592 – the Duke of Parma could have been in London within a week of coming ashore.

As the Spanish anchored off Calais, 4,000 militia based in Dover deserted, possibly because they were unpaid, but more probably through abject fear. The port’s defences were hastily stiffened by importing 800 Dutch musketeers, who promptly mutinied.

The loyalty of the inhabitants of Kent was uncertain. Informers reported that some rejoiced “when any report was [made] of [the Spaniards’] good success and sorrowed for the contrary” while others declared the Spanish “were better than the people of this land”.

As is the case in any invasion planning, the Spanish identified potential collaborators, and enemy leaders to be captured. (Elizabeth was to be detained unharmed and sent to Rome).

Those “heretics and schismatics” who faced a sticky end if Spain was victorious included the Earl of Leicester, his brother the Earl of Warwick and brother-in-law the Earl of Huntingdon Lord Burghley, “Secretary Walsingham”, Sir Christopher Hatton, and Lord Hunsdon. These were “the principal devils that rule the court and are the leaders of the [Privy] Council”.

The list of “Catholics and friends of his majesty in England” was headed by “the Earl of Surrey, son and heir of the Duke of Norfolk, (actually the Earl of Arundel) now a prisoner in the Tower” and “Lord Vaux of Harrowden, a good Catholic, a prisoner in the Fleet (prison)”.

The four potential collaborators in Norfolk included Sir Henry Bedingfield, “formerly the guardian of Queen Elizabeth the pretended queen of England, during the whole time that his majesty was in England”.

The document reported that “the greater part of Lancashire is Catholic, the common people particularly, with the exception of the Earl of Derby and the town of Liverpool”. Westmorland and Northumberland remained “really faithful to his majesty”.

Amphibious landings, however, are the most risky of all military operations, with everything dependent on weather and tides. And the English fleet would have to be destroyed first.

Robert Hutchinson is a historian specialising in the Tudor period. He has previously written biographies of Henry VIII and Francis Walsingham.