Demonstrators attack police vans during a protest against the poll tax in 1990. The British Library exhibition shows the Magna Carta as a call to stand up for your rights by any means necessary. Photograph: REX/REX

The most powerful work of art in the gripping Magna Carta exhibition portrays a king being attacked by peasants. They come at Henry I with scythe, fork and shovel, turning the tools of their daily work into crudely effective weapons.

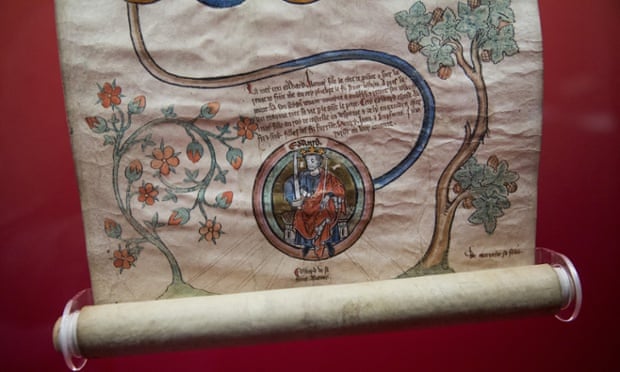

This surreal masterpiece of medieval art is a depiction of a royal nightmare: uneasy lies the head that wears the crown. There was no revolution against Henry I, although a few generations later, in 1215, the reviled King John would be forced at swordpoint to grant freedoms to his people and the Magna Carta would be born.

Yet this superbly drawn illumination from the Chronicle of Worcester, dating from about 1140, portrays Henry menaced by the peasants in his sleep. It is said that he was plagued by nightmares after he broke promises to his people. In other scenes in this sinewy cartoon strip, Henry’s knights loom over his bed with their swords, and bishops raise their croziers threateningly over his unconscious form.

It is a startling window on early medieval Britain. Who knew that British kings so long ago had nightmares about revolution?

Two teeth and a finger bone belonging to John, extracted by antiquarians from his tomb in Worcester Cathedral, are this exhibition’s strangest relics. Together with a cast of his tomb effigy they testify to the enduring charisma of kingship. And yet this king was so hated for soaking his subjects for cash that in 1215 his own barons forced him to put his royal seal on a document limiting his power.

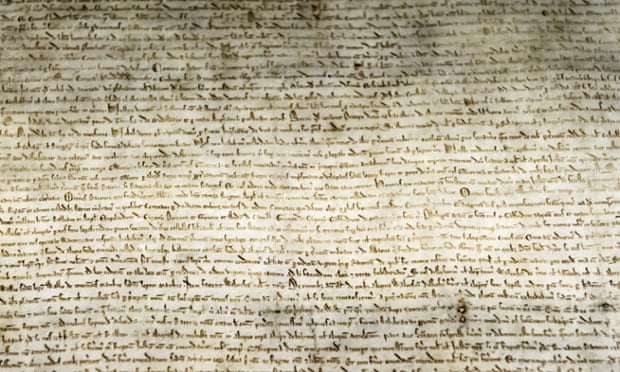

The Magna Carta is a document and a myth. But what is its real message? The wondrous array of materials here, which include an original copy of the US Bill of Rights lent by Congress, as well as a French revolutionary painting of the Declaration of the Rights of Man, made me think that far from a venerable relic of the British middle way, the Magna Carta is a call to stand up for your rights by any means necessary.

Generations of jurists and libertarians have revered it as an ancient guarantor of freedom and justice. In a South African courtroom in 1964, Nelson Mandela stated his respect for the document. Yet the true lesson of Magna Carta’s history as revealed here is that rights have to be fought for and the roots of democracy are bloodsoaked.

We do not base modern politics on Plato’s Republic or Machiavelli’s Discourses but the Magna Carta is still quoted against everything from control orders to European integration. This bald document has more bite than all the classics of political thought. That is because it is not an abstract philosophical meditation on the nature of justice and freedom, but a blunt assertion of what rulers cannot do. The barons of 13th-century England gave human rights a tough, no-nonsense, visceral force.

A medieval sword, with an occult inscription on its blade, is on display among the illuminated manuscripts and royal seals to remind us that the Magna Carta was obtained through violence. The 13th-century Melrose Chronicle recognised that the Magna Carta turned the world upside down. It said: “The people desired to be masters of the king.”

No comments:

Post a Comment