Ancient Origins

Stuart Brookes /The Conversation

The Last Kingdom – BBC’s historical drama set in the time of Alfred the Great’s war with the Vikings – has returned to our screens for a second series. While most attention will continue to focus on the fictional hero Uhtred, his story is played out against a political background where the main protagonist is the brooding and bookish mastermind Alfred the Great, vividly portrayed in the series by David Dawson.

But was Alfred the Great really that great? If we judge him on the basis of new findings in landscape archaeology that are radically changing our understanding of warfare in the Viking Age, it would seem not. It looks like Alfred was a good propagandist rather than a visionary military leader.

Alfred the Great's statue at Winchester. Hamo Thornycroft's bronze statue erected in 1899. (Odejea/CC BY 3.0)

The broad outline of King Alfred’s wars with the Vikings is well known. Oft defeated by the great army of the Vikings, he took refuge in a remote part of Somerset before rallying the English army in 878 and defeating the Vikings at Edington. It was not this one victory that made Alfred great, according to his biographer Asser, but the military reforms Alfred implemented after Edington. In creating a system of strongholds, a longer-serving army and new naval forces, Asser argues that Alfred put in place systems which meant that the Vikings would never win again. In doing so, he secured his legacy.

It is a well-known story, but how accurate is it? Research by a team at UCL and another at the University of Nottingham into the archaeology and place-name evidence for late Anglo-Saxon civil defence presents a slightly different picture.

Alfred the Great plots the capture of the Danish fleet. (Public Domain)

Alfred’s strongholds

Many towns claim to have been founded by Alfred as part of his plan for defending England. This idea rests largely on a text known as the Burghal Hidage, which lists the names of 33 strongholds (in Old English burhs) across southern England and the taxes assigned to their garrisons, recorded as numbers of hides (a unit of land). According to the list, under Alfred a military machine was created whereby no fewer than 27,000 men, some 6% of the total population, were assigned to the defence and maintenance of what has been described as “fortress Wessex”.

Strongholds listed in the Burghal Hidage. Author provided.

Over the past 40 years, much archaeological evidence has been gathered about the Burghal Hidage strongholds, many of which were former Roman towns or Iron Age hill forts that were reused or refurbished as Anglo-Saxon military sites. Others were new burhs raised with an innovative design that imitated the regular Roman plan.

It has been argued that the latter represent an “Alfredian” vision of urban planning. But the evidence doesn’t entirely bear this out. For example, in Winchester radiocarbon and archaeomagnetic dating suggests the new urban plan was probably built around 840–80, almost certainly, therefore, before Alfred’s victory of 878 and probably before he even became king. Excavations in Worcester, by contrast, show that the distinctive “Alfredian” street plan there only came into use in the late tenth or early 11th century, around 100 years after Alfred’s death.

Archaeological evidence shows that many Bughal Hidage strongholds started as defensive sites which only later developed into towns. Sometimes this occurred at the same location, but in the case of strongholds at Iron Age hill forts, such as Burpham (Sussex), Chisbury (Wiltshire), and Pilton (Devon), more suitable locations for defended towns were sought nearby. While the general development of early emergency measures – where defence policy was determined by inaccessibility and expediency – are testimony to Alfred’s civil defence strategy, the more long-term development of purpose-built towns, around which England’s economy and administration became organised, only took place during the reigns of Alfred’s successors.

Late Anglo-Saxon Winchester showing the characteristic arrangement of streets and town defences often accredited to Alfred the Great. Author provided.

Landscapes of defence

The major strongholds listed in the Burghal Hidage have received much attention, but landscape research is also now helping to provide a fuller picture, allowing us to identify important early route-ways and river crossing-points.

Place-names containing such compounds as Old English here-pæð or fyrd-weg, both meaning “army road”, are especially important. But place-names also suggest the existence of elaborate systems of beacons and lookouts, often spaced at regular intervals, visible to each other and to known strongholds, and providing control over important route-ways. Written sources and archaeological excavation confirm that beacons were in use in the early 11th century. Landscape analysis is also helping to identify the important mustering sites, crucial to mobilisation, without which the military system would not have worked.

Aerial view of the Burghal Hidage site of Wallingford with the Thames in partial flood. Outline of the Saxon ramparts and ‘Alfredian’ street plan is clear. Image courtesy of the Environmental Agency, Author provided.

Putting all this evidence together makes it likely that Alfred the Great’s military innovations were part of a continuing development, that started in the eight century in Mercia and continued long after his death. Alfred built on existing structures, at first using what was already in place, such as hilltop defences and mustering sites of the eighth and early ninth centuries, but many of the most innovative developments in defensive organisation clearly occurred in the reign of his son, Edward the Elder (899–924). Indeed, the little closely datable evidence that can be gleaned from the major burhs, all points to a long chronology of stronghold construction.

Alfred’s defensive genius lay not in the creation of burhs, then, but in the way he adapted earlier strategies to suit the drastically altered military demands of the Viking age. His first steps towards a reliable and more constant system of military service ensured the continuous availability of troops. But the glories afforded him in popular imagination as the architect of “fortress Wessex” no longer, it seems, stand.

St. Alfred the Great. (CC BY SA 3.0)

Top Image: Alfred the Great. (19th century). Source: Public Domain

The article, originally titled ‘New research indicates that Alfred the Great probably wasn’t that great’ by Stuart Brookes was originally published on The Conversation and has been republished under a Creative Commons license.

Showing posts with label fortress. Show all posts

Showing posts with label fortress. Show all posts

Wednesday, April 12, 2017

Sunday, April 9, 2017

Crusader Shipwreck Yields Coins and Other Artifacts from the Final Years of a Holy Land Fortress

Ancient Origins

Marine archaeologists have discovered some intriguing artifacts in the wreck of a ship belonging to the Crusaders in Acre, Israel. It dates to the time of the valiant last stand by the few remaining knights and mercenaries who died heroically defending the walls of the last powerful Christian fortress in the Holy Land.

The Geopolitical Significance of Acre in the Past

The Crusader kingdom in the Holy Land began to collapse in the later part of the 13th century. The fall of Jaffa and Antioch in 1268 to the Muslims forced Louis IX to undertake the Eighth Crusade (1270), which was cut short by his death in Tunisia. The Ninth Crusade (1271–72), was led by Prince Edward, who landed at Acre but retired after concluding a truce. In 1289, Tripoli fell to the Muslims, leaving Acre as the only remaining Christian fortress in the Holy Land. Capturing Acre was extremely crucial from a geopolitical and strategical point of view for the Mamluks, as Western European forces had used the site for a very long time as a landing point for European soldiers, knights, and horses, as well as an international commercial spot for the export of sugar, spices, glass, and textiles back to Europe.

The fall of Tripoli to the Mamluks, April 1289. This was a battle towards the end of the Crusades and preceded the siege of Acre. (Public Domain)

During the spring of 1291, the Egyptian sultan Al-Ashraf Khalil with his immense forces (over 100,000 cavalry and foot soldiers) attacked the fortress in Acre and for six weeks the siege dragged on - until the Mamluks took the outer wall. The Military Orders drove back the Mamluks temporarily, but three days later the inner wall was breached. King Henry escaped, but the bulk of the defenders and most of the citizens perished in the fighting or were sold into slavery. The surviving knights fell back to their fortress, resisting for ten days, until the Mamluks broke through, killing them. Western Christianity would never again establish a firm foothold in the Middle East.

The Siege of Acre. The Hospitalier Master Mathieu de Clermont defending the walls in 1291. (Public Domain)

The Discovery of the Wreck at Acre

Marine archaeologists from Haifa University, Prof. Michal Artzy and Dr. Ehud Galili, led the exploration of the Crusader shipwreck. The ship was severely damaged during the construction of the modern harbor of Acre, while the surviving wreckage includes some ballast-covered wooden planks, the ship’s keel, and a few sections of its hull. Carbon dating showed that the wood used to construct the hull dates to between 1062 AD and 1250 AD. Among the keel and planks that remain, thirty impressive golden coins were also found according to an article appearing in Haaretz.

Florins found in the Crusader shipwreck of Acre harbor. (Israel Antiquities Authority)

Robert Kool of Israel Antiquities Authority identified the coins as "florins," which were used in Florence during the 1200’s. Historical firsthand sources from the Siege of Acre recorded that nobles and merchants used such coins to bribe the owners of the boats in order to buy their fleet. In addition to the golden coins found near the wreckage, marine archaeologists also found imported ceramic bowls and jugs from southern Italy, Syria, and Cyprus; corroded pieces of iron, mostly nails, and anchors. Excavation work in the area began last year and the impressive new finds are now coming to light.

Glazed Crusader bowl with human face, found in Acre. (Michal Artzy)

Top Image: A grapnel anchor found in Acre harbor by marine archaeologists. (Ehud Galili) Gold coin issued by John III, Holy Emperor of Nicaea III (1222-1254 AD), found in Acre. (Zinman Institute of the University of Haifa and the Deutsche Orden) And Glazed Crusader bowl and horseshoe, imported from Europe. (Michal Artzy)

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Marine archaeologists have discovered some intriguing artifacts in the wreck of a ship belonging to the Crusaders in Acre, Israel. It dates to the time of the valiant last stand by the few remaining knights and mercenaries who died heroically defending the walls of the last powerful Christian fortress in the Holy Land.

The Geopolitical Significance of Acre in the Past

The Crusader kingdom in the Holy Land began to collapse in the later part of the 13th century. The fall of Jaffa and Antioch in 1268 to the Muslims forced Louis IX to undertake the Eighth Crusade (1270), which was cut short by his death in Tunisia. The Ninth Crusade (1271–72), was led by Prince Edward, who landed at Acre but retired after concluding a truce. In 1289, Tripoli fell to the Muslims, leaving Acre as the only remaining Christian fortress in the Holy Land. Capturing Acre was extremely crucial from a geopolitical and strategical point of view for the Mamluks, as Western European forces had used the site for a very long time as a landing point for European soldiers, knights, and horses, as well as an international commercial spot for the export of sugar, spices, glass, and textiles back to Europe.

The fall of Tripoli to the Mamluks, April 1289. This was a battle towards the end of the Crusades and preceded the siege of Acre. (Public Domain)

During the spring of 1291, the Egyptian sultan Al-Ashraf Khalil with his immense forces (over 100,000 cavalry and foot soldiers) attacked the fortress in Acre and for six weeks the siege dragged on - until the Mamluks took the outer wall. The Military Orders drove back the Mamluks temporarily, but three days later the inner wall was breached. King Henry escaped, but the bulk of the defenders and most of the citizens perished in the fighting or were sold into slavery. The surviving knights fell back to their fortress, resisting for ten days, until the Mamluks broke through, killing them. Western Christianity would never again establish a firm foothold in the Middle East.

The Siege of Acre. The Hospitalier Master Mathieu de Clermont defending the walls in 1291. (Public Domain)

The Discovery of the Wreck at Acre

Marine archaeologists from Haifa University, Prof. Michal Artzy and Dr. Ehud Galili, led the exploration of the Crusader shipwreck. The ship was severely damaged during the construction of the modern harbor of Acre, while the surviving wreckage includes some ballast-covered wooden planks, the ship’s keel, and a few sections of its hull. Carbon dating showed that the wood used to construct the hull dates to between 1062 AD and 1250 AD. Among the keel and planks that remain, thirty impressive golden coins were also found according to an article appearing in Haaretz.

Florins found in the Crusader shipwreck of Acre harbor. (Israel Antiquities Authority)

Robert Kool of Israel Antiquities Authority identified the coins as "florins," which were used in Florence during the 1200’s. Historical firsthand sources from the Siege of Acre recorded that nobles and merchants used such coins to bribe the owners of the boats in order to buy their fleet. In addition to the golden coins found near the wreckage, marine archaeologists also found imported ceramic bowls and jugs from southern Italy, Syria, and Cyprus; corroded pieces of iron, mostly nails, and anchors. Excavation work in the area began last year and the impressive new finds are now coming to light.

Glazed Crusader bowl with human face, found in Acre. (Michal Artzy)

Top Image: A grapnel anchor found in Acre harbor by marine archaeologists. (Ehud Galili) Gold coin issued by John III, Holy Emperor of Nicaea III (1222-1254 AD), found in Acre. (Zinman Institute of the University of Haifa and the Deutsche Orden) And Glazed Crusader bowl and horseshoe, imported from Europe. (Michal Artzy)

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Sunday, February 12, 2017

Archaeologists to Explore Mysterious Underground Structure at the Desert Fortress of Masada

Ancient Origins

A team of archaeologists from Tel Aviv University have returned to Masada in Israel, after a 11-year hiatus, in order to excavate previously unexplored areas of the desert mountain fortress, including a mysterious underground structure. Once a pleasure palace for Herod the Great, Masada is most well-known for the deaths of around 960 Jewish rebels and their families in 74 AD, who chose to commit suicide rather than be captured or slaughtered by the Romans.

Fresh Explorations of an Ancient Treasure

For the first time since 2006, a Tel Aviv University team, headed by Roman-period archaeologist Guy Stiebel, have launched new excavations at the UNESCO World Heritage Site, examining previously untouched areas of the legendary desert mountain fortress. “This is the next generation,” Stiebel told The Times of Israel, adding that his team plan to excavate new sections of the Jewish rebel dwellings, as well as a garden constructed by Herod, “Our intention is to further explore a mysterious underground structure that was detected in the earliest (1924) aerial photographs of the site. The building has remained hitherto unexplored.”

Dr Stiebel did not add any further information about the underground structure and what it may have been used for. But it is possible that it was used as a hideout or escape route during the Siege of Masada.

Dr. Stiebel expressed his excitement to return to the site after an eleven-year absence in his statements to i24news, “A lifetime would not suffice to get a glimpse of all the hidden beauties of Masada. Its magic is not just in the military equipment, it is also in small things.” Even though several experts believe that more than 95% of Masada’s potential has already been exploited, Stiebel believe that its core is yet to be discovered, including the mysterious underground structure that lies there and is waiting to be closely explored.

A model of the northern palace as Masada (public domain)

The Dramatic History of the Desert Fortress of Masada The ancient fortress of Masada stands on the eastern edge of the Judean Desert. With a sheer drop of more than 400 meters to the western shore of the Dead Sea, the view from the top of the plateau would have been breath-taking. Yet, the silence of the ruins belies one of the most interesting episodes in Jewish history.

While the first structures on Masada were apparently built by the Hasmonaean king, Alexander Jannaeus in the early 1st century BC, most of the structures were constructed by Herod the Great during the latter half of that century. Having conquered Masada in 42 BC, Masada became a safe refuge for Herod and his family during their long struggle for power in Israel. Apart from being a fortress, Masada was also a pleasure palace for Herod. For instance, it was designed along the lines of a Roman villa, and several amphorae found in Masada’s storerooms had Latin inscriptions, indicating that they contained wine imported all the way from Italy. After the death of Herod in 4 BC, Masada became a military outpost, and housed a Roman garrison, presumably of auxiliary forces.

A Roman siege ramp seen from above ( CC by SA 3.0 )

In 66 AD, the first Jewish Revolt broke out. The most comprehensive record of this record can be found in Flavius Josephus’ The Jewish War. According to Josephus, a group of Jewish zealots, the Sicarii succeeded in seizing Masada from the Romans in the winter of 66 AD. After the fall of Jerusalem in 70 AD, Masada was filled up with refugees who escaped and were determined to continue the struggle against the Romans. Hence, Masada became a base for their raiding operations for the following two years. In the winter of 73/74 AD, the governor of Judaea, Flavius Silva, decided to conquer Masada and crush the resistance once and for all. According to Josephus Flavius, the only historical source for the battle, the Jewish rebels committed mass suicide before Roman troops stormed the battlements, even though many historians and archaeologists have challenged the historicity of that account.

“Next Generation” Excavation Begins

The first excavations in the area took place in the period from 1963 to 1965 under former IDF chief of staff and archaeologist Yigal Yadin. The dry desert climate allowed the preservation of classy frescoes and organic remains belonging to the Jewish rebels who holed up on the mountaintop. The archaeological team will be posting updates and photos from the site on its Facebook page

Top image: Aerial view of the desert fortress of Masada ( CC by SA 4.0 )

By Theodoros Karasavvas

A team of archaeologists from Tel Aviv University have returned to Masada in Israel, after a 11-year hiatus, in order to excavate previously unexplored areas of the desert mountain fortress, including a mysterious underground structure. Once a pleasure palace for Herod the Great, Masada is most well-known for the deaths of around 960 Jewish rebels and their families in 74 AD, who chose to commit suicide rather than be captured or slaughtered by the Romans.

Fresh Explorations of an Ancient Treasure

For the first time since 2006, a Tel Aviv University team, headed by Roman-period archaeologist Guy Stiebel, have launched new excavations at the UNESCO World Heritage Site, examining previously untouched areas of the legendary desert mountain fortress. “This is the next generation,” Stiebel told The Times of Israel, adding that his team plan to excavate new sections of the Jewish rebel dwellings, as well as a garden constructed by Herod, “Our intention is to further explore a mysterious underground structure that was detected in the earliest (1924) aerial photographs of the site. The building has remained hitherto unexplored.”

Dr Stiebel did not add any further information about the underground structure and what it may have been used for. But it is possible that it was used as a hideout or escape route during the Siege of Masada.

Dr. Stiebel expressed his excitement to return to the site after an eleven-year absence in his statements to i24news, “A lifetime would not suffice to get a glimpse of all the hidden beauties of Masada. Its magic is not just in the military equipment, it is also in small things.” Even though several experts believe that more than 95% of Masada’s potential has already been exploited, Stiebel believe that its core is yet to be discovered, including the mysterious underground structure that lies there and is waiting to be closely explored.

A model of the northern palace as Masada (public domain)

The Dramatic History of the Desert Fortress of Masada The ancient fortress of Masada stands on the eastern edge of the Judean Desert. With a sheer drop of more than 400 meters to the western shore of the Dead Sea, the view from the top of the plateau would have been breath-taking. Yet, the silence of the ruins belies one of the most interesting episodes in Jewish history.

While the first structures on Masada were apparently built by the Hasmonaean king, Alexander Jannaeus in the early 1st century BC, most of the structures were constructed by Herod the Great during the latter half of that century. Having conquered Masada in 42 BC, Masada became a safe refuge for Herod and his family during their long struggle for power in Israel. Apart from being a fortress, Masada was also a pleasure palace for Herod. For instance, it was designed along the lines of a Roman villa, and several amphorae found in Masada’s storerooms had Latin inscriptions, indicating that they contained wine imported all the way from Italy. After the death of Herod in 4 BC, Masada became a military outpost, and housed a Roman garrison, presumably of auxiliary forces.

A Roman siege ramp seen from above ( CC by SA 3.0 )

In 66 AD, the first Jewish Revolt broke out. The most comprehensive record of this record can be found in Flavius Josephus’ The Jewish War. According to Josephus, a group of Jewish zealots, the Sicarii succeeded in seizing Masada from the Romans in the winter of 66 AD. After the fall of Jerusalem in 70 AD, Masada was filled up with refugees who escaped and were determined to continue the struggle against the Romans. Hence, Masada became a base for their raiding operations for the following two years. In the winter of 73/74 AD, the governor of Judaea, Flavius Silva, decided to conquer Masada and crush the resistance once and for all. According to Josephus Flavius, the only historical source for the battle, the Jewish rebels committed mass suicide before Roman troops stormed the battlements, even though many historians and archaeologists have challenged the historicity of that account.

“Next Generation” Excavation Begins

The first excavations in the area took place in the period from 1963 to 1965 under former IDF chief of staff and archaeologist Yigal Yadin. The dry desert climate allowed the preservation of classy frescoes and organic remains belonging to the Jewish rebels who holed up on the mountaintop. The archaeological team will be posting updates and photos from the site on its Facebook page

Top image: Aerial view of the desert fortress of Masada ( CC by SA 4.0 )

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Monday, January 23, 2017

Kumbhalgarh: The Great Wall You Have Never Heard Of (and it is NOT in China)

Ancient Origins

The wall that encircles the ancient fort of Kumbhalgarh is one of the biggest secrets in India, and possibly the entire planet. Guarding a massive fort that contains over 300 ancient temples, the little-known wall was said to be constructed almost 500 years ago in tandem with Kumbhalgarh Fort itself. However, a retired archaeologist now suggests another immense wall may be even older.

Historians Refer to it as the “Great Wall” of India

Most of us are aware of the Great Wall of China, but apparently, many also ignore a massive wall that stands tall in India. The fort of Kumbhalgarh is the second most significant fort of Rajasthan after Chittorgarh and extends to the amazing length of 36 kilometers (22.5 miles).

The wall that surrounds it, which history buffs love calling the “Great Wall of India”, is speculated to be 80 kilometers (50 miles) long, a fact that would make it India’s longest fortification and the second longest wall worldwide, only behind China’s.

Kumbhalgarh Fort and wall. (CC BY SA 3.0)

Ιn 2013, at the 37th session of the World Heritage Committee held in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, Kumbhalgarh Fort, alongside five different fortifications of Rajasthan, was proudly pronounced a UNESCO World Heritage Site under the gathering Hill Forts of Rajasthan. However, it still remains widely unknown for some reason, despite its massive construction and beautiful architecture.

At its widest sections, the wall is 15 meters (49.2 ft.) thick, and impressively built with thousands of stone bricks and decorative flourishes along the top - making this just as attractive as a tourist destination as it once was effective as a deterrent.

The Wall’s History and Mysteries Work on Kumbhalgarh only began in 1443, nearly fifty years before Columbus sailed the Atlantic Ocean and discovered another, even larger, wall in China. Situated in the state of Rajasthan in the west of India, constructions started by the local Maharana, Rana Kumbha in that year.

Walls of the Kumbhalgarh Fort. (Shivam Chaturvedi/CC BY SA 3.0)

It took over a century to construct the wall and it was later enlarged in the 19th century. The Kumbhalgarh Fort, protected by the massive wall, was built high on a hill so it could dominate and observe the landscape from a distance. Altogether the wall has seven gateways, and it is believed that during the reign of the Maharana, the wall held so many lamps that it enabled the local farmers to work both day and night.

Even more precious to the inhabitants of Kumbhalgarh, the wall mainly protected over 360 temples.

Jain Temple in the Kumbalgarh fortress. (CC BY SA 4.0)

Now, Narayan Vyas, a man who made several surveys of a wall between Bhopal and Jabalpur after retiring from the Archaeological Survey of India a decade ago, believes that that the temple relics and the wall could be even older than most historians think, dating somewhere from the 10th to 11th century AD, when warrior clans ruled the heart of India

Two entwined snakes stand at one end of the wall, near Gorakhpur, India. (Pratik Chorge/HT PHOTO)

He told Hindustan Times, “This could have been the border of the Parmar kingdom,” referring to the Rajputs that dominated west-central India between the 9th and 13th centuries. He suggests that the wall may have been used to mark their territory against the Kalachuris, “They fought a lot, and the wall was probably a Parmar effort to keep them out.”

Vyas also admits that this is just speculation for now and that further research is needed in order to prove these theories to be historically accurate, “All we need is evidence to confirm what we suspect – that we’ve found the remnants of a 1,000-year-old realm,” Vyas says.

Questions

Rahman Ali, a historian who has written a book on the Parmar sites and visited them in 1975, might admit that he didn’t examine it too closely, but says that the wall still didn’t look Parmar to him. He states:

“There is a tendency to ascribe everything old from this region to the Parmars, but the dynasty would have been crumbling in the 12th century, not building massive walls. The standardized stone barricades may be much younger, perhaps even 17th-century British-made; but these areas weren’t important to the Raj. Why would they build a long wall and abandon it?”

Examining the immense wall. (Pratik Chorge/HT Photo)

Is it India’s Great Wall? Although the mystery remains and heated debates between historians may have only started, it is certain that locals are extremely proud of this giant structure and their history. They are also optimistic for the area’s future when it comes to tourism.

Top Image: Aerial view of a portion of the Kumbhalgarh wall. Source: Heman kumar meena/CC BY SA 3.0

By Theodoros Karasavvas

The wall that encircles the ancient fort of Kumbhalgarh is one of the biggest secrets in India, and possibly the entire planet. Guarding a massive fort that contains over 300 ancient temples, the little-known wall was said to be constructed almost 500 years ago in tandem with Kumbhalgarh Fort itself. However, a retired archaeologist now suggests another immense wall may be even older.

Historians Refer to it as the “Great Wall” of India

Most of us are aware of the Great Wall of China, but apparently, many also ignore a massive wall that stands tall in India. The fort of Kumbhalgarh is the second most significant fort of Rajasthan after Chittorgarh and extends to the amazing length of 36 kilometers (22.5 miles).

The wall that surrounds it, which history buffs love calling the “Great Wall of India”, is speculated to be 80 kilometers (50 miles) long, a fact that would make it India’s longest fortification and the second longest wall worldwide, only behind China’s.

Kumbhalgarh Fort and wall. (CC BY SA 3.0)

Ιn 2013, at the 37th session of the World Heritage Committee held in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, Kumbhalgarh Fort, alongside five different fortifications of Rajasthan, was proudly pronounced a UNESCO World Heritage Site under the gathering Hill Forts of Rajasthan. However, it still remains widely unknown for some reason, despite its massive construction and beautiful architecture.

At its widest sections, the wall is 15 meters (49.2 ft.) thick, and impressively built with thousands of stone bricks and decorative flourishes along the top - making this just as attractive as a tourist destination as it once was effective as a deterrent.

The Wall’s History and Mysteries Work on Kumbhalgarh only began in 1443, nearly fifty years before Columbus sailed the Atlantic Ocean and discovered another, even larger, wall in China. Situated in the state of Rajasthan in the west of India, constructions started by the local Maharana, Rana Kumbha in that year.

Walls of the Kumbhalgarh Fort. (Shivam Chaturvedi/CC BY SA 3.0)

It took over a century to construct the wall and it was later enlarged in the 19th century. The Kumbhalgarh Fort, protected by the massive wall, was built high on a hill so it could dominate and observe the landscape from a distance. Altogether the wall has seven gateways, and it is believed that during the reign of the Maharana, the wall held so many lamps that it enabled the local farmers to work both day and night.

Even more precious to the inhabitants of Kumbhalgarh, the wall mainly protected over 360 temples.

Jain Temple in the Kumbalgarh fortress. (CC BY SA 4.0)

Now, Narayan Vyas, a man who made several surveys of a wall between Bhopal and Jabalpur after retiring from the Archaeological Survey of India a decade ago, believes that that the temple relics and the wall could be even older than most historians think, dating somewhere from the 10th to 11th century AD, when warrior clans ruled the heart of India

Two entwined snakes stand at one end of the wall, near Gorakhpur, India. (Pratik Chorge/HT PHOTO)

He told Hindustan Times, “This could have been the border of the Parmar kingdom,” referring to the Rajputs that dominated west-central India between the 9th and 13th centuries. He suggests that the wall may have been used to mark their territory against the Kalachuris, “They fought a lot, and the wall was probably a Parmar effort to keep them out.”

Vyas also admits that this is just speculation for now and that further research is needed in order to prove these theories to be historically accurate, “All we need is evidence to confirm what we suspect – that we’ve found the remnants of a 1,000-year-old realm,” Vyas says.

Questions

Rahman Ali, a historian who has written a book on the Parmar sites and visited them in 1975, might admit that he didn’t examine it too closely, but says that the wall still didn’t look Parmar to him. He states:

“There is a tendency to ascribe everything old from this region to the Parmars, but the dynasty would have been crumbling in the 12th century, not building massive walls. The standardized stone barricades may be much younger, perhaps even 17th-century British-made; but these areas weren’t important to the Raj. Why would they build a long wall and abandon it?”

Examining the immense wall. (Pratik Chorge/HT Photo)

Is it India’s Great Wall? Although the mystery remains and heated debates between historians may have only started, it is certain that locals are extremely proud of this giant structure and their history. They are also optimistic for the area’s future when it comes to tourism.

Top Image: Aerial view of a portion of the Kumbhalgarh wall. Source: Heman kumar meena/CC BY SA 3.0

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Monday, November 21, 2016

Unearthing the 1,000-Year-Old Story of a Rare Viking Toolbox

Ancient Origins

The discovery of a rare 1,000-year-old Viking toolbox containing 14 unique iron tools caused excitement during recent excavations at an old Viking fortress. The toolbox was unearthed in a small lump of soil at Denmark's fifth Viking ring fortress: Borgring. It is the first direct evidence that people actually lived at the site.

Science Nordic journalist Charlotte Price Persson became an archaeologist for a day and joined the team of researchers to help clear away the dirt and expose the iron tools.

The soil containing the artifacts was removed from the site of one of the four gates at Borgring. The researchers suggest that the tools could have belonged to people who lived in the fortress. It contains an amazing collection of tools which were used around the 10 th century AD.

Lead archaeologist Nanna Holm decided to take a better look before excavation began on the tools. As she told Science Nordic: “We could see that there was something in the layers [of soil] around the east gate. If it had been a big signal from the upper layers then it could have been a regular plough, but it came from the more ‘exciting’ layers. So we dug it up and asked the local hospital for permission to borrow their CT-scanner.”

The scans allowed the researchers to see the shapes of the tools and they realized that the toolbox itself was gone – the wood had rotted away over time. However, the placement of the objects suggests that the wooden box was replaced with soil. The discovery is exceptionally rare. Tools made of iron were very expensive and precious to the Vikings. It is strange that nobody had found them before and melted the objects down to repurpose the iron.

CT Scan of the Viking toolbox. ( videnskab.dk) The archaeologists believe that an analysis of the artifacts will help them to understand what type of craftsman owned them. For now, they suppose that the spoon drills and drawplate could have been used to produce thin wire bracelets. But, this kind of drill was also used to make holes in wood – suggesting that it could have also been a carpenter’s toolbox. Moreover, the location of the artifacts by the eastern gate of the fortress provides more information on the tools’ history. They could have been used after a fire that torched the fortress’ north and east gates in the second half of the 10th century. The team also found a room near the gate which could have been a workshop or used for housing a craftsman. It measures about 30-40 square meters (322-430 sq. ft.), and had its own fireplace. The researchers speculate that the tools were buried underground when the gate collapsed – explaining why the recovery of the valued iron objects would have been difficult.

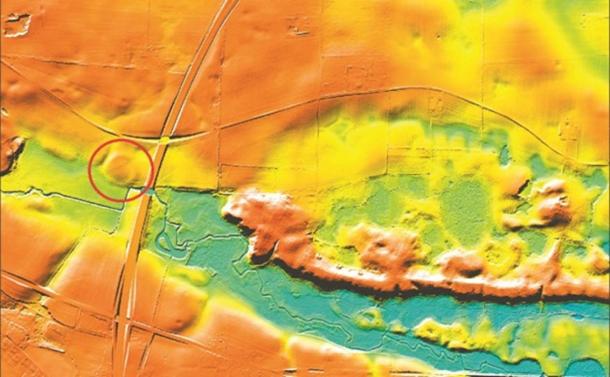

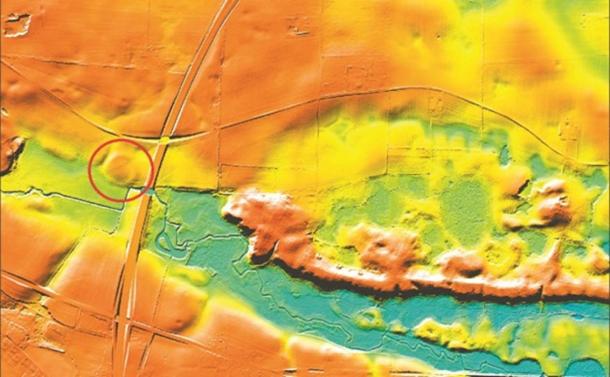

Aerial photo of Vallø Borgring. This is an edited version of a satellite photo with added hill shade. The arrow is pointing at a site which has a clear circular form. (Danskebjerge/ CC BY SA 3.0 ) Now the researchers want to scan the tools by X-ray. That should help Holm’s team to identify exactly what the tools are. She already has some ideas, for example, that one of the spoon drills may be a pair of pliers or tweezers. It is planned that the tools will be put on display next year, although the artifacts need conservation work before they will be ready to be exhibited.

Thinglink interactive image: https://www.thinglink.com/scene/850665224653504512

Thinglink interactive image: https://www.thinglink.com/scene/850665224653504512

Top Image: Example of a Viking toolbox that was found in 1936 at the bottom of the former lake Mästermyr, island of Gotland. Source: Christer Åhlin/SHMM

By Natalia Klimczak

Lead archaeologist Nanna Holm decided to take a better look before excavation began on the tools. As she told Science Nordic: “We could see that there was something in the layers [of soil] around the east gate. If it had been a big signal from the upper layers then it could have been a regular plough, but it came from the more ‘exciting’ layers. So we dug it up and asked the local hospital for permission to borrow their CT-scanner.”

The scans allowed the researchers to see the shapes of the tools and they realized that the toolbox itself was gone – the wood had rotted away over time. However, the placement of the objects suggests that the wooden box was replaced with soil. The discovery is exceptionally rare. Tools made of iron were very expensive and precious to the Vikings. It is strange that nobody had found them before and melted the objects down to repurpose the iron.

CT Scan of the Viking toolbox. ( videnskab.dk) The archaeologists believe that an analysis of the artifacts will help them to understand what type of craftsman owned them. For now, they suppose that the spoon drills and drawplate could have been used to produce thin wire bracelets. But, this kind of drill was also used to make holes in wood – suggesting that it could have also been a carpenter’s toolbox. Moreover, the location of the artifacts by the eastern gate of the fortress provides more information on the tools’ history. They could have been used after a fire that torched the fortress’ north and east gates in the second half of the 10th century. The team also found a room near the gate which could have been a workshop or used for housing a craftsman. It measures about 30-40 square meters (322-430 sq. ft.), and had its own fireplace. The researchers speculate that the tools were buried underground when the gate collapsed – explaining why the recovery of the valued iron objects would have been difficult.

Aerial photo of Vallø Borgring. This is an edited version of a satellite photo with added hill shade. The arrow is pointing at a site which has a clear circular form. (Danskebjerge/ CC BY SA 3.0 ) Now the researchers want to scan the tools by X-ray. That should help Holm’s team to identify exactly what the tools are. She already has some ideas, for example, that one of the spoon drills may be a pair of pliers or tweezers. It is planned that the tools will be put on display next year, although the artifacts need conservation work before they will be ready to be exhibited.

Thinglink interactive image: https://www.thinglink.com/scene/850665224653504512

Thinglink interactive image: https://www.thinglink.com/scene/850665224653504512Top Image: Example of a Viking toolbox that was found in 1936 at the bottom of the former lake Mästermyr, island of Gotland. Source: Christer Åhlin/SHMM

By Natalia Klimczak

Tuesday, July 12, 2016

The Viking Fortress that Burned: Arson Investigator to Analyze 1,000-Year-Old Crime Scene

Ancient Origins

Archaeologists have asked police to send an arson investigator to the site of a 1,000-year-old Danish castle that apparently was deliberately burned, possibly as an act of retaliation against Viking King Harald Bluetooth, who was said to have driven his men too hard.

Archaeologists say they have found clear evidence that someone set fire to the Viking castle Vallø Borgring near Køge not far from Copenhagen. They are hoping to shed more light on the cold case with modern fire-investigation techniques. According to an article in the CPHPost.dk, the arsonists set fires at the northern and eastern gates of the castle, which was constructed in a ring.

Researchers say the half-constructed castle may have belonged to King Harald Bluetooth, who reigned in the late 900s. Historical documents state that the king drove his army too hard, so his men retaliated in a riot during which he was killed.

“Our theory right now is that other powerful men in the country attacked the castle and set fire to the gates,” Ulriksen is quoted as saying.

The researchers intend to ask the fire investigator to bring in dogs to sniff out human remains in the earth and possibly to help uncover other evidence of arson.

“Borgring” means ring fortress. It was built as a 10- to 11-meter-wide (32.8 to 36 feet) stockade with pointed wooden poles, excavations have shown. The fortress is 145 meters (475.7 feet) in diameter and visible from the air (see photo above and at the top of the article).

Five other Viking ring fortresses have been found in Denmark, possibly all built on the command of one person, but when this castle was discovered in 2014, it was the first in 60 years.

“The four other circular fortresses have been dated to the reign of Harald Bluetooth in the late 900s. The construction of this fortress is very similar to the one found in Hobro, and thus it is likely that Harald Bluetooth was the builder too, the Danish Castle Centre believes,” says CPHPost.dk in another article.

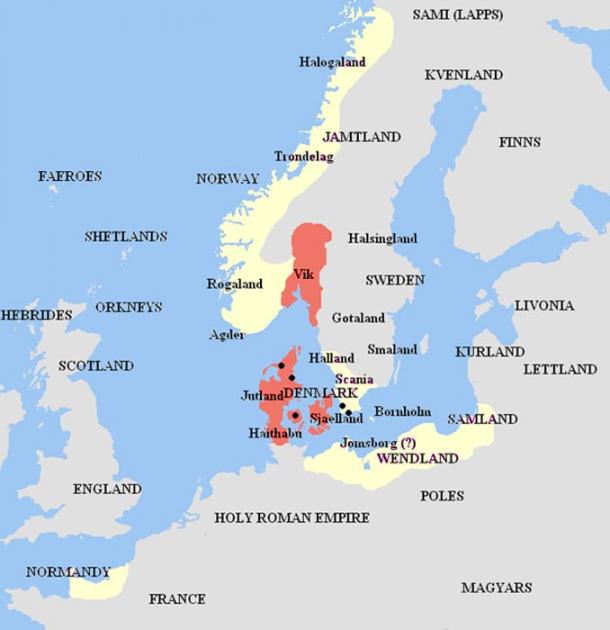

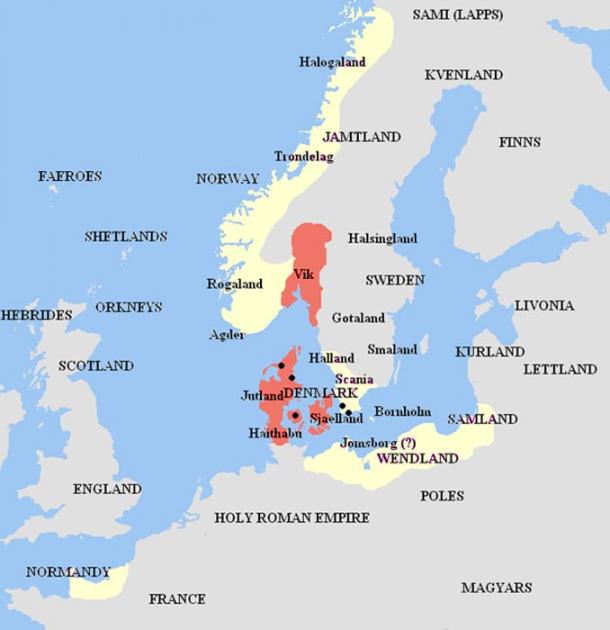

Carbon dating has confirmed the castle near Køge dates to around the time of Bluetooth. He reigned from around 958 to his death in 985, possibly at the hands of his son Sweyn Forkbeard. Harald was the son of Gorm the Old and Thyra Dannebod, founders of a new line of royalty who ruled from northern Jutland, the Danish peninsula that juts into the North Sea toward Sweden and Norway.

His name was used in the Bluetooth standard that connects electronic devices without wires.

Top image: Photo from a modern-day Viking fire festival (Photo: warosu.org)

By Mark Miller

Archaeologists say they have found clear evidence that someone set fire to the Viking castle Vallø Borgring near Køge not far from Copenhagen. They are hoping to shed more light on the cold case with modern fire-investigation techniques. According to an article in the CPHPost.dk, the arsonists set fires at the northern and eastern gates of the castle, which was constructed in a ring.

Drone operators discovered the fortress (circled in red) in 2014. (photo: Museum Sydøstdanmark)

Jens Ulriksen, head of the excavations at the fortress, told DR Nyheder: “All indications are that there has been a fire set at the gates of the castle. The outer posts of the east gate are completely charred, and there are signs of burning on the inside.”Researchers say the half-constructed castle may have belonged to King Harald Bluetooth, who reigned in the late 900s. Historical documents state that the king drove his army too hard, so his men retaliated in a riot during which he was killed.

“Our theory right now is that other powerful men in the country attacked the castle and set fire to the gates,” Ulriksen is quoted as saying.

Another view of the landscape and the ring fortress without infrared (Photo: Danskebjerge)

It was possibly the last structure built by Bluetooth, researchers say, because construction on it was only half done when it burned.The researchers intend to ask the fire investigator to bring in dogs to sniff out human remains in the earth and possibly to help uncover other evidence of arson.

“Borgring” means ring fortress. It was built as a 10- to 11-meter-wide (32.8 to 36 feet) stockade with pointed wooden poles, excavations have shown. The fortress is 145 meters (475.7 feet) in diameter and visible from the air (see photo above and at the top of the article).

Five other Viking ring fortresses have been found in Denmark, possibly all built on the command of one person, but when this castle was discovered in 2014, it was the first in 60 years.

“The four other circular fortresses have been dated to the reign of Harald Bluetooth in the late 900s. The construction of this fortress is very similar to the one found in Hobro, and thus it is likely that Harald Bluetooth was the builder too, the Danish Castle Centre believes,” says CPHPost.dk in another article.

A runestone with an inscription to Harald Bluetooth (Wikimedia Commons/Jürgen Howaldt)

“Although, there were Vikings in other countries, these circular fortresses are unique to Denmark. Many have given up hope that there were many of them left,” Viking age scholar Lasse C.A. Sonne said in 2014.Carbon dating has confirmed the castle near Køge dates to around the time of Bluetooth. He reigned from around 958 to his death in 985, possibly at the hands of his son Sweyn Forkbeard. Harald was the son of Gorm the Old and Thyra Dannebod, founders of a new line of royalty who ruled from northern Jutland, the Danish peninsula that juts into the North Sea toward Sweden and Norway.

Harald's kingdom in red and his vassals and allies in yellow, as described in medieval Scandinavian sources (Wikimedia Commons/Bryangotts)

Harald continued the unification of Denmark begun by Gorm. He also was one of the principal figures in the conversion of the Danes to Christianity. Around 970 he conquered Norway. His descendants would rule England for a time.His name was used in the Bluetooth standard that connects electronic devices without wires.

Top image: Photo from a modern-day Viking fire festival (Photo: warosu.org)

By Mark Miller

Friday, September 12, 2014

Ancient Viking Fortress Reveals 'Fierce Warriors' Were Decent Architects

By Elizabeth Palermo

The Vikings weren't just a fierce band of warriors with cool headgear. A new archaeological discovery in Denmark suggests that these notorious fighters were also decent builders.

Archaeologists on the Danish island of Zealand recently discovered a Viking fortress that likely dates back to the 10th century A.D. It's the first time in 60 years that such a fortress has been unearthed in Denmark, the researchers said.

"The Vikings have a reputation as [fierce Norse warriors] and pirates. It comes as a surprise to many that they were also capable of building magnificent fortresses," Søren Sindbæk, a professor of medieval archeology at Aarhus University in Denmark, said in a statement. The discovery of the new fortress provides an opportunity for archaeologists to gain even more knowledge about Viking wars and conflicts, Sindbæk added. [Fierce Fighters: 7 Secrets of Viking Seamen]

Prior to this latest discovery, three other Viking fortresses were discovered in Denmark. These structures, named Fyrkat, Aggersborg and Trelleborg, are known collectively as the "Trelleborg" fortresses.

"We recognize the 'Trelleborg' fortresses by the precise circular shape of the ramparts and by the four massive gates that are directed at the four corners of the compass," said Nanna Holm, curator of the Danish Castle Centre in Denmark, who helped identify the site of the newly unearthed fortress. "Our investigations show that the new fortress was perfectly circular and had sturdy timber along the front. We have so far examined two gates, and they agree exactly with the 'Trelleborg' plan."

The fortress, located south of the capital city of Copenhagen, is huge, Holm said. It spans nearly 476 feet (145 meters) across, longer than 1.5 football fields.

Archaeologists long suspected that a fourth Trelleborg fortress might exist on the island of Zealand, according to Sindbæk, who has studied these structures for years. And the site of Vallø, now part of the Zealand Region on the east coast of Zealand, is an ideal place for the Vikings to have built such a structure, Sindbæk said.

During the 10th century, Vallø marked the spot where two main roads met, Sindbæk said. It also overlooked the Køge river valley, which at that time was a navigable fjord and one of the best natural harbors on the island, Sindbæk added.

Suspecting a fortress might be buried beneath Vallø, the team of archaeologists used advanced laser and magnetic tools to determine the structure's exact location. The team included Helen Goodchild from the University of York, in the United Kingdom.

"By measuring small variation[s] in the Earth's magnetism, we can identify old pits or features without destroying anything," Sindbæk said. "In this way, we achieved an amazingly detailed 'ghost image' of the fortress in a few days. Then we knew exactly where we had to put in excavation trenches to get as much information as possible about the mysterious fortress."

Once the team had uncovered the hidden structure, Holm said the researchers noticed a telltale sign that the fortress they had suspected was indeed buried there: At the north end of the site, the team found massive, charred oak posts, which the archaeologists said they think were once gates that had been burned down. The team is using radiocarbon dating and dendrochronology, or tree-ring dating, to determine the precise age of the charred wood, an effort that could help archaeologists figure out exactly when the fortress was constructed.

"We are eager to establish if the castle will turn out to be from the time of King Harald Bluetooth, like the previously known fortresses, or perhaps a former king's work," said Holm. "If we can establish exactly when the fortress was built, we may be able to understand the historic events which the fortress was part of."

Live Science

Researchers explore the Viking fortress, discovered on the Vallø estate, near Køge, Denmark.

Credit: The Danish Castle Centre

Credit: The Danish Castle Centre

Archaeologists on the Danish island of Zealand recently discovered a Viking fortress that likely dates back to the 10th century A.D. It's the first time in 60 years that such a fortress has been unearthed in Denmark, the researchers said.

"The Vikings have a reputation as [fierce Norse warriors] and pirates. It comes as a surprise to many that they were also capable of building magnificent fortresses," Søren Sindbæk, a professor of medieval archeology at Aarhus University in Denmark, said in a statement. The discovery of the new fortress provides an opportunity for archaeologists to gain even more knowledge about Viking wars and conflicts, Sindbæk added. [Fierce Fighters: 7 Secrets of Viking Seamen]

Prior to this latest discovery, three other Viking fortresses were discovered in Denmark. These structures, named Fyrkat, Aggersborg and Trelleborg, are known collectively as the "Trelleborg" fortresses.

"We recognize the 'Trelleborg' fortresses by the precise circular shape of the ramparts and by the four massive gates that are directed at the four corners of the compass," said Nanna Holm, curator of the Danish Castle Centre in Denmark, who helped identify the site of the newly unearthed fortress. "Our investigations show that the new fortress was perfectly circular and had sturdy timber along the front. We have so far examined two gates, and they agree exactly with the 'Trelleborg' plan."

The fortress, located south of the capital city of Copenhagen, is huge, Holm said. It spans nearly 476 feet (145 meters) across, longer than 1.5 football fields.

Archaeologists long suspected that a fourth Trelleborg fortress might exist on the island of Zealand, according to Sindbæk, who has studied these structures for years. And the site of Vallø, now part of the Zealand Region on the east coast of Zealand, is an ideal place for the Vikings to have built such a structure, Sindbæk said.

During the 10th century, Vallø marked the spot where two main roads met, Sindbæk said. It also overlooked the Køge river valley, which at that time was a navigable fjord and one of the best natural harbors on the island, Sindbæk added.

Suspecting a fortress might be buried beneath Vallø, the team of archaeologists used advanced laser and magnetic tools to determine the structure's exact location. The team included Helen Goodchild from the University of York, in the United Kingdom.

"By measuring small variation[s] in the Earth's magnetism, we can identify old pits or features without destroying anything," Sindbæk said. "In this way, we achieved an amazingly detailed 'ghost image' of the fortress in a few days. Then we knew exactly where we had to put in excavation trenches to get as much information as possible about the mysterious fortress."

Once the team had uncovered the hidden structure, Holm said the researchers noticed a telltale sign that the fortress they had suspected was indeed buried there: At the north end of the site, the team found massive, charred oak posts, which the archaeologists said they think were once gates that had been burned down. The team is using radiocarbon dating and dendrochronology, or tree-ring dating, to determine the precise age of the charred wood, an effort that could help archaeologists figure out exactly when the fortress was constructed.

"We are eager to establish if the castle will turn out to be from the time of King Harald Bluetooth, like the previously known fortresses, or perhaps a former king's work," said Holm. "If we can establish exactly when the fortress was built, we may be able to understand the historic events which the fortress was part of."

Live Science

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)